Improvement

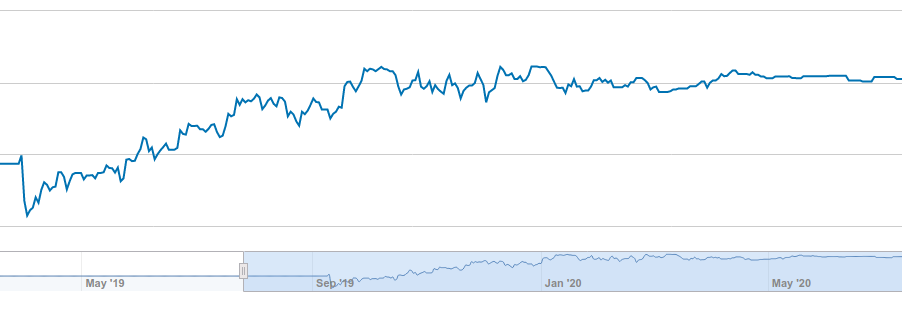

I play a lot of online chess, mostly quick games on my phone. Here’s my rating in blitz games1 on lichess over the last year.

My Lichess blitz rating Aug19-Jul20

You’ll see that I play quite a lot, and that I improved until about January, and then flattened out.

You don’t improve at things by default.

If this were just about chess it wouldn’t be interesting. But in most areas of life it’s very possible to do something for a long time and stagnate. We have an assumption that we’ll keep improving but that just doesn’t seem to be true.

If I wanted to improve at chess, what would I do?

- Hire a tutor.

- Study chess books.

- Study the greats, closely related to the previous.

- Do exercises (eg tactical puzzles).

- Go over my games in more depth afterwards.

- Play longer games, where I would be forced to think more instead of playing by instinct.

Hire a tutor

Buck Shlegeris writes about his experience hiring tutors to give him an introduction to particular fields. In general, I think hiring professionals to help you is underrated. I’d like to consider the difference between a tutor and a coach: it might be related to the difference Agnes Callard identifies here between instruction, coaching and advice.

Study chess books

Chess is fairly unique among domains in having a lot of literature specifically devoted to self-study and self-improvement. For most scholarly pursuits grad school is an apprenticeship in how to do this, and the literature in the field is mostly inaccessible without having received that in-person training.

Stripe Press recently republished Hamming’s The Art of Doing Science and Engineering which seems to recognize and partly address this problem. I’ve also heard good things about Polya’s How to Solve It.

So for most fields what you need to do is first figure out how professionals who have received this training improve (eg by reading papers) and then identify how you get to a place where you too can use this method.

Or, a tutor can help not only by introducing you to material but also by teaching you how to use it.

Study the greats

One of the things a course of study will do is show you how the exceptional people in that field perform and practice. Chess, again, is great for this because games are available, and many chess books involve careful study of past games. And many grandmasters have written about their thought process.

For many other things apprenticeship is the most information-dense way to achieve it, but you can pick up glimpses from interviews, or short pieces they’ve written. You want to understand the work itself, the process they go through to improve, and their analysis of individual pieces of work.

Do exercises

Recently, one of my favorite questions to bug people with has been “What is it you do to train that is comparable to a pianist practicing scales?” If you don’t know the answer to that one, maybe you are doing something wrong or not doing enough.

Most things in life do not come with these kinds of exercises already prepared, and part of the work is to break complex tasks down into components and then figure out how to improve those.

Cowen also has a post listing his answers to this question. They’re great, but they span a few categories, not just doing exercises.

Recap past work

I have a friend who works in product at tech companies. He keeps a list of every A/B test he’s ever run across several companies in his decade-long career. Great players of any sport remember their careers with vivid detail, because the study what they’ve done again and again.

Writing is well-suited for this because the revision process involves frequent re-reading of your own work. A full application of this principle, though, would be looking back at the final product, the process itself, and the history of edits, to identify issues with the process as well as the work.

Play longer games

This is particularly interesting – it’s the only one that applies within the activity itself, describes a way of doing the activity rather than an accessory to it.

A general truth seems to be that you should spend relatively little of your time doing the activity, and most of your time on improving at it.

For later

Look at the things you do from this perspective. What are the areas of life where you want better skills? How can you break those down and work on them?

Comments (0)

To leave a comment on this post, send me an email.

Revision History

(About)